EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

AI tools have become ubiquitous, entering many facets of everyday life. More often than not, “artificial intelligence” models are presented as fully automated, having dispensed with the need for human intervention. The human workers who train, test, and maintain AI models and act as the first line of defense against model failures are made visible only occasionally. Media coverage sometimes emerges of hundreds of Indian workers1 who remotely ensure the checkout process goes smoothly while creating the illusion of automation at Amazon Go stores and African content moderators2 who make social media platforms safer at great personal cost. But these stories only scratch the surface of the labor that underpins every part of the AI production process.

Despite being touted as the definitive technological breakthrough of this century, the conditions under which AI models and tools are produced by data workers, in a highly opaque and fissured global supply chain, are still underexplored. Studies of data workers in the Global South have begun to fill gaps in knowledge about the low-paid outsourced labor behind AI, but less is known about U.S. data workers’ conditions.

In this report, we begin to address this gap through a study of the working conditions of U.S.-based data workers, conducted by AWU-CWA and TechEquity.These workers are essential to the development of tools and models developed by big tech companies, but are employed by complex webs of contractors in the U.S.-based sections of the global AI supply chain. Combining data from a survey of 160 data workers with insights from 15 in-depth interviews, we’ve found that the poor working conditions seen in the Global South are also widespread in data work in the U.S.

We identify four broad themes that should concern policymakers:

- Workers struggle to make ends meet. 86% of surveyed workers worry about meeting their financial responsibilities, and 25% of respondents rely on public assistance, primarily food assistance and Medicaid. Nearly two-thirds of respondents (66%) report spending at least three hours weekly sitting at their computers waiting for tasks to be available, and 26% report spending more than eight hours waiting for tasks. Only 30% of respondents reported that they are paid for the time when no tasks are available. Workers reported a median hourly wage of $15 and a median workweek of 29 hours of paid time, which equates to annual earnings of $22,620.

- Workers perform critical, skilled work but are increasingly hamstrung by lack of control over the work process, which results in lower work output and, in turn, higher-risk AI systems. More than half of the workers who are assigned an average estimated time (AET) to complete a task felt that AETs are often not long enough to complete the task accurately. 87% of respondents report they are regularly assigned tasks for which they are not adequately trained.

- With limited or no access to mental health benefits, workers are unable to safeguard themselves even as they act as a first line of defense, protecting millions of people from harmful content and imperfect AI systems. Only 23% of surveyed workers are covered by health insurance from their employer.

- Deeply involved in every aspect of building AI systems, workers recognize the wide range of risks that these systems pose to themselves and to society at large. Fifty-two percent of surveyed workers believe they are training AI to replace other workers’ jobs, and 36% believe they are training AI to replace their own jobs. 74% were concerned about AI’s contribution to the spread of disinformation, 54% concerned about surveillance, and 47% concerned about the use of AI to suppress free speech, among other issues.

These findings, which suggest that U.S.-based data workers face similar working conditions as data workers in the Global South, challenge our understanding of the global AI supply chain. Rather than a supply chain where low-wage work is offshored to countries with lax labor standards while high-wage work flourishes in the U.S., the AI industry is driving a race to the bottom for workers across industrialized and developing countries alike.

Even as workers struggle in jobs in which they often do not see opportunities for advancement and as the limitations of current AI technology are made increasingly visible, the big tech companies that drive AI investment on the promise of a future of supercharged productivity continue to generate record profits.

As policymakers debate what guardrails need to be in place to govern this emerging technology, it is vital that they pay attention to the perspectives of data workers themselves, who are closest to the production of AI. However, workers face significant structural barriers to having their voices heard. AI companies and their contractors must respect the rights of workers to take collective action, exercise freedom of association, and bargain to improve their workplaces, without the fear of violating restrictive non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). To create safer and higher-quality AI systems, data workers must be treated as skilled workers with the expertise required to improve these systems.

Are you a North American data worker? Tell us your story.

INTRODUCTION

When asked what he would like people to know about his work, Kirn Gill II said, “If there's anything I wanted the general public to know, it is that there are low paid people who are not even treated as humans — just little more than employee ID numbers — out there making the 1 billion dollar, trillion dollar AI systems that are supposed to lead our entire society and civilization into the future.” Kirn is a Search Quality Rater working on Google products at Telus, an AI vendor. An AI Writing Evaluator at another tech contractor called GlobalLogic, who wished to remain anonymous, wrote about feeling dehumanized and dispensable: “I am treated like a robot; it's obvious they would prefer that I were a robot. Robots don't need medications and such.”

Kirn Gill II, Search Quality Rater for Google products at Telus (an AI vendor)

AI systems are built on the essential labor of Kirn and tens of thousands of other data workers like him in the U.S. and globally, who train, test, and maintain the AI tools that have become ubiquitous in daily life. Yet, the workers who perform the labor necessary to create “artificial intelligence” are rarely centered in the conversation as big tech companies drive the AI hype cycle and benefit from the astronomical valuations associated with the AI boom.

The AI employment landscape is fissured and opaque. Big tech companies in the U.S. and Europe subcontract data work through long chains of suppliers and online platforms.3 Research examining global AI supply chains has revealed how data workers in the global South4, including Kenya, India, Venezuela, the Philippines, and elsewhere, perform the human labor behind purportedly automated systems, often for low wages under traumatizing conditions.

Conventional wisdom dictates that employers seek to reduce costs by outsourcing work to regions with lower wages and minimal labor regulations, while domestic workers thrive in well-paid jobs. Testimony from Kirn and other data workers surveyed and interviewed for this report reveals that the major tech companies’ labor strategies upend this dynamic by implementing poor working conditions for U.S.-based workers in the domestic market as well. The purpose of this report is to bring visibility to the working conditions faced by data workers in the U.S., who are also part of the global AI workforce, and reveal how multi-trillion-dollar companies treat workers without whom AI as we know it would not exist.

Following a brief background on the big tech companies’ rapidly rising operating profits in Section III, Section IV of this report delves into how data workers underpin every stage of the AI production process. Next, Section V describes the data workers surveyed for this report and what motivates them to undertake data work. Section VI presents the working conditions experienced by workers in the AI production process, including wages, control over the work process, and mental health impacts of AI work. Section VII presents workers’ insights into the broader societal risks potentially posed by AI, including potential job displacement. Section VIII concludes the report, highlighting data workers’ efforts to improve their working conditions and identifying the significant need for policymakers to support AI workers’ labor rights as one component of broader societal accountability for AI development.

“If there's anything I wanted the general public to know, it is that there are low paid people who are not even treated as humans — just little more than employee ID numbers — out there making the 1 billion dollar, trillion dollar AI systems that are supposed to lead our entire society and civilization into the future.” |

|---|

“I am treated like a robot; it's obvious they would prefer that I were a robot. Robots don't need medications and such.” |

|---|

SKYROCKETING PROFITS FOR TECH GIANTS

Tech giants are making massive bets on generative AI, integrating it into their existing products and selling access to the foundation models to other businesses and consumers. In the second quarter of 2025, the three biggest AI infrastructure companies – Alphabet, Microsoft, and Amazon – continued to claim rapid advances in AI products they said are being well-received by the public.

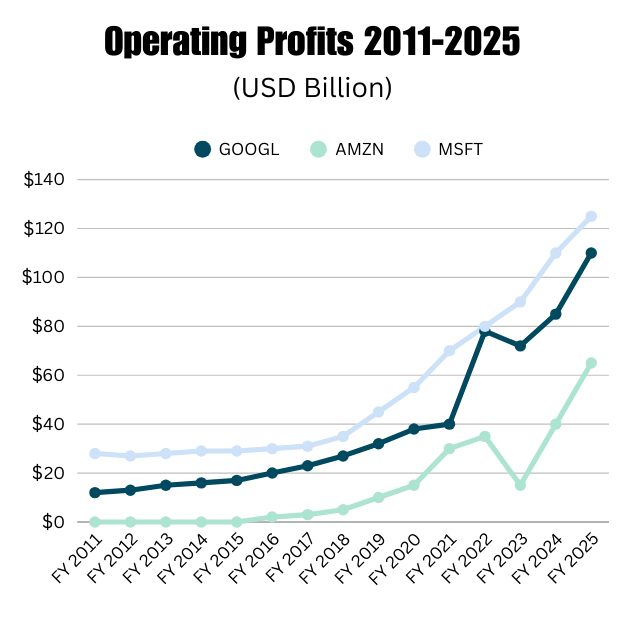

While analysts speculate over the ultimate profitability of AI experiments, the companies have been able to rely on their existing businesses to drive growth as demand for data hosting and services continues to expand.5 Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon generate growth through software monopolies and massive investments in data centers, with pre-tax profits increasing astronomically in the past 10 years (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Operating Profit for Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft, 2011 to 2025

METHODS

| This report is based on a mixed-methods study conducted by AWU-CWA and TechEquity between April and July 2025, combining insights from a survey administered to 160 data workers and in-depth interviews with 15 of the surveyed workers from a cross-section of job titles and companies. The survey instrument was piloted with Alphabet Workers Union (AWU) members before being posted on major social media platforms and circulated through worker networks. Workers who were open to being interviewed could indicate their willingness through a survey response. The interviews were conducted on Zoom and lasted an average of one hour. Workers surveyed and interviewed for this report spoke passionately about the need to address the poor pay and conditions facing the shadow workforce that makes AI possible. Throughout the report, we highlight their voices with quotes drawn from both interviews and written surveys. Some workers agreed to be identified by their full names, but most workers are kept anonymous to protect them against the risk of retaliation for speaking out. |

WHAT DO DATA WORKERS DO?

Figure 2. Word cloud of top 20 job titles reported by survey respondents6

The workers surveyed for this report have a wide range of job titles, including search quality rater, content writer, AI trainer, LLM evaluator, internet safety evaluator, data aggregator, and many more. Workers’ descriptions of their day-to-day responsibilities provide insight into how central their work is to functional AI systems.

AI systems are not only the creation of the high-profile engineers who have been offered headline-grabbing multimillion-dollar pay packages. But tech companies provide little transparency about the vast number of data workers who populate, train, and maintain these systems. It is important to underline the complexity of AI production processes and the interconnected and iterative nature of different types of data work.

Workers' job functions can be generally categorized into:

Data Collection

Although much of the data that is used to train AI models is collected through the purchase of datasets, web-scraping, or open-source repositories, data workers are occasionally engaged in collecting data or even contributing data.

Content Moderation

A globally dispersed and largely contract workforce of content moderators trawls through hours of content generated on social media platforms, acting as a first line of defense7 against harmful content that includes violence, hate speech, misinformation, and graphic images. These workers protect millions of users and create trustworthy and safe digital spaces at great cost to their own mental and physical health. Much of the data scraped from social media platforms to contribute to large language models (LLMs) has been subject to the content standards of major tech platforms that are moderated by these workers.

Data Annotation

Data that is scraped from the web and from social media platforms is then labeled, filtered, and organized by data workers for AI systems to learn how to infer outputs correctly for a wide variety of use cases.

Model Training

Workers also play a central role when AI systems are based on unlabeled data. Through processes such as RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback) and SFT (supervised fine-tuning), workers provide feedback loops that give positive and negative signals to align an AI system with the preferences of clients. Training by humans is also essential to teach AI systems how to perform tasks whose goals are difficult to specify - like identifying emotions or biases encoded in text. In such situations, human experts create labeled examples, demonstrating how the LLM ought to respond in various use cases.

Kirn Gill II, the Telus worker, explains: “I am what they call a search quality rater. Google will come up with two different versions of their search algorithm. They will run the same search through both of them, and they will present this result side by side. We know how to rank it based off of how well it meets the needs of the user and…the overall page quality.” Other workers explained how they used their skills to rate the responses of AI tools, often struggling with frustration at not being able to provide nuanced feedback that could actually improve the tool.

Model Evaluation

Before an AI system is deployed and even when it’s in use, continuous testing, also referred to as validation or verification, is carried out by workers through prompt-response processes. This can include processes such as red-teaming8, where workers stress test AI models through provocative prompts to uncover potentially biased, inaccurate, hallucinatory (invented by the AI system), or toxic content, as well as checking a model’s accuracy by comparing its output to benchmarked standards. Such testing and maintenance work makes AI systems better, keeps them secure, and limits their ability to cause widespread harm.

AI Fauxtomation

Although workers are able to train AI systems to get better at mimicking human responses, these systems are still far from perfect. Systems that claim to be automated9 have been found to rely on workers10 to carry out their central functions. From AI assistants who turned out to be human11 to self-checkout stores that were managed remotely12 by workers in India and ‘autonomous’ vehicles that are being guided by technicians hundreds of miles away13, evidence abounds that AI systems sustain the illusion of being automated by depending heavily on human labor. Workers who are impersonating AI14 are at the same time generating data that is used to train and perfect the system they are impersonating.

WHO MAKES UP THE WORKFORCE THAT TRAINS AI?

The companies that produce foundational models rely on likely tens of thousands of data workers to train their AI systems.15 There is not sufficient publicly available data to determine the exact size of this global workforce, and it has been challenging for researchers to examine this question. These workers are employed by a web of vendors and subcontractors. For example, Google’s global workforce is more than fifty percent temporary workers, contractors, or vendor employees.16

The decision to outsource this critically important but labor-intensive part of the AI development process keeps workers at a remove from the tech titans paying for their labor, creating major barriers to addressing workplace concerns. Building on the concept of fissured workplaces17 where the lead firm limits its liability for the employment conditions of workers producing its good or services through subcontracting, franchising and other forms of legal separation, this has been referred to as AI-enabled fissuring18: “Employers have expanding options for restructuring tasks and production in a way that permits outsourcing them to vendors, platforms, or freelance employment contracts… These jobs are organized in complex global production networks of lead firms, suppliers, and platforms, with power significantly concentrated at major tech companies such as Meta, Alphabet, and OpenAI/Microsoft. The ‘fissuring’ of AI labor has both an organizational and spatial dimension, as lead firms outsource data enrichment and content moderation work to domestic and international vendors.”

Data workers in this report

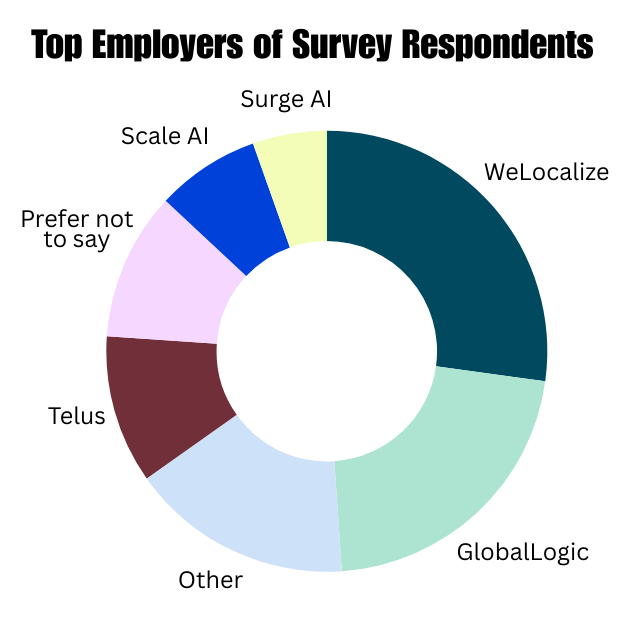

In our survey of data workers, respondents reported being employed by 28 individual vendors, with the largest number employed by the vendors Telus, GlobalLogic, Scale AI, and WeLocalize.19

In the case of GlobalLogic, a subsidiary of Japanese industrial firm Hitachi Group, some workers are employed directly by GlobalLogic while others are employed by at least seven subcontractors that act as staffing firms.20 GlobalLogic may use this arrangement to force subcontractors to bid against each other on labor and other costs. This creates a patchwork of employment practices that results in inequities and job insecurity. GlobalLogic’s subcontractors often employ workers as either temps, who get no paid holidays or vacation time, or contractors, who get no paid time off at all, even sick time.21

In the survey, 23% of respondents said they work as 1099 independent contractors for vendors like Scale AI. 1099 independent contractors lack the basic legal rights of a W-2 employee, including minimum wage, overtime, workers’ compensation insurance, and protection from antidiscrimination and disability rights laws.22

Survey respondents reported a median tenure of one year at their current employer. Only 21% had worked at their employer for more than three years.

Of the workers who reported their gender, 52% were women, 39% men, 6% genderqueer/nonbinary, and 2% transgender. Of the workers who reported their racial/ethnic background, 80% were White, 10% Hispanic/Latino, 9% Asian/Pacific Islander, 8% Black, and 3% Native American.

Workers value flexible and accessible work

Survey respondents value the remote nature and flexible hours of data jobs, which is a reason many want to stay in their positions – if they can improve the pay and conditions.

Workers spoke in interviews about how data work jobs enable people who have accessibility issues and cannot undertake conventional types of employment at a workplace due to ill health, mental or physical disabilities, or care responsibilities to earn an income. A Cynet contractor for GlobalLogic who works on Google projects said, “I worked an on-campus job, but I got COVID three times, and each time, the long COVID symptoms were worse. I felt it wasn’t worth the chance any longer, so I transitioned back to working online… [Some of the people who do this job] have a condition or disability where they need this job and it’s not just a paycheck.”

Workers appreciated the ability to take breaks and set their own schedules so they could accommodate their healthcare needs and family responsibilities. Despite the fact that many of them work remotely, workers also formed connections with their co-workers, which they valued. A Digitive worker observed: “I’ve met really good people. I’ve made friends. The people I work with directly, you get to know them and you make connections even though it's virtual.”

While workers with disabilities may be uniquely attracted to aspects of AI data jobs, they also face challenges due to lack of accommodations.

Thirty-four percent of survey respondents reported having a disability, but only 7% (three out of 42) reported having an accommodation at their job. |

|---|

One Telus worker based in Virginia said that their job “could be perfect” for them if some of their workplace concerns were addressed. Another worker wished that these jobs could offer better quality of work for those who depend on them.

"Some of the people who do this job have a condition or disability where they need this job and it’s not just a paycheck.” |

|---|

WHAT ARE THE WORKING CONDITIONS FOR THE PRODUCTION OF AI?

According to the responses from our survey and interviews, the workers who train AI say their wages are too low to make ends meet, their own training is inadequate, and their working conditions are stressful and insecure, which could negatively impact the quality of AI output.

Workers struggle to make ends meet

Workers are paid low wages

Across the entire survey sample, workers reported a median hourly wage of $1523 and a median workweek of 29 hours of paid time24, which equates to annual earnings of $22,620. Nearly half of the sample (45%) are part-time W-2 employees who make a median wage of $14.60. Among the 19% of surveyed workers classified as 1099 independent contractors, respondents reported a median hourly wage of $21, suggesting that this arrangement is not limited to highly-paid, specialized positions.25

Less than half of workers (45%) rely only on their data job, with 37% reporting one additional job and 18% reporting two or more additional jobs.

Only 23% of respondents are covered by health insurance from their employer. As a result of these low wages and inadequate benefits, eighty-six percent of surveyed workers worry about meeting their financial responsibilities often (63%) or sometimes (26%). Twenty-five percent of respondents rely on public assistance, primarily food assistance and Medicaid.

Twenty-two percent of respondents report they have experienced homelessness because they could not afford to move or find housing that they could afford. |

|---|

A Digitive worker who subcontracts for GlobalLogic on Google projects describes a disconnect between their conditions and the promises made by big tech, explaining, “I’m still on ACA [a health plan through the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance marketplace] even though I work for a trillion-dollar company. If we’re so needed for this AI development, you sure aren’t treated like you are… they know the job market sucks, so what are you gonna do? We’re replaceable; they sell the idea ‘Oh, you are at Google: you get great things,’ but I don't get holiday pay, sick time, days off, any PTO, any of the things even GlobalLogic employees get.”

Kirn Gill II, who lives in Missouri, believes that when the minimum wage goes up, his employer will exit the state: “Right here in the U.S., they pay as low as possible. Telus pays between $12 and $14 an hour. I'm paid $14 in Missouri, and I expect when the minimum wage goes up (to $15) at the end of the year that I get let go from that because they decide we're not going to pay anyone that much. Because right now the minimum wage is $13.75.”

Describing very low wages in a major city, a Telus worker in Virginia reported, “I do not feel fairly compensated. The pay level is abysmal for the amount of work we put in. I set my schedule, but it’s a big dedication: I work 8 hours a day, it’s just from home. I’m only getting $14/hr before tax, so that’s about $12/hr after tax: that’s not sustainable where I live in Richmond, Virginia, and it’s my main source of income… this is not sustainable for where I live: I’m below the poverty line and I can’t pay for things I need.”

An Internet Safety Evaluator employed by Telus in Pennsylvania explained she makes ends meet, but barely: “I stay home and work while my daughter plays and naps, and I take breaks when needed. It's impossible to pay for childcare and work... The cost of meat is going extremely high, so we buy it when it's on sale, portion it, and then freeze it. We spend $3800 in bills a month and barely have anything else left over. We are drowning. The economy is horrible right now.”

Workers described moving back in with parents, going without needed healthcare, and being unable to afford a car. An AI trainer with a master’s degree and 15 years of work experience as a nonprofit fundraiser spoke about moving in with her parents in order to make ends meet after suffering from neck injuries. Another worker, a GlobalLogic Data Rater in Texas, explained, "I can't afford both rent and a car, so I don't have a car currently. This only works because I work remotely, and affects other aspects of my life. For example, grocery shopping and maintaining social ties/mental health are difficult. I also rely heavily on family contributions for unexpected expenses like medical visits."

Waiting for work

Most workers surveyed (85%) are expected to be on-call for periods when there are no tasks available to complete. More than half of respondents (66%) report spending at least three hours weekly sitting at their computers waiting for tasks to be available, and 26% report spending more than 8 hours waiting for tasks. Only 30% of respondents reported that they are paid for the time when no tasks are available.

On a platform like MTurk, “when you are looking for work, you can sit on MTurk all day browsing for work, and that is time spent unpaid,” according to a worker in Michigan who has worked on multiple platforms, including MTurk.

Krista Pawloski, a Michigan-based worker at Amazon MTurk, confirmed, “good work [on MTurk] goes really quick; There’s a lot more hunting, which is unpaid job search time.”

Krista Pawloski, Amazon MTurk worker

The survey asked workers if they had ever calculated their effective hourly pay, including time waiting for tasks, and of the 22 respondents who had done so, 73% believed they had earned less than the minimum wage for some period of time.

"We’re replaceable; they sell the idea ‘Oh, you are at Google: you get great things,’ but I don't get holiday pay, sick time, days off, any PTO, any of the things even GlobalLogic employees get.” |

|---|

Unpaid training time

Twenty-six percent of respondents reported they were not paid for training time. There was a much higher prevalence of unpaid training among 1099 independent contractors (56%) compared to W2 employees (25%), particularly full-time W2 employees (10%).

Even more commonly, workers are not paid for the time it takes to test to qualify for jobs, with 53% of respondents reporting they are not paid for testing. A worker who has worked for multiple platforms, including Outlier, said, “I don’t know how they figure out pay; a lot of times, you take qualification tests, but that’s unpaid, so you could spend time taking and passing a test and you could qualify and then you don’t get the work so you did that work unpaid.”

"You could spend time taking and passing a test and you could qualify and then you don’t get the work so you did that work unpaid.” |

|---|

Loss of access to work

AI vendors often have automated systems that flag workers who fail to meet specific metrics and may suspend workers until they are retested.

Nearly a quarter (31%) of respondents reported they have experienced being suspended, of whom 88% were not paid during the suspension period. |

|---|

Krista Pawloski explained her experience of suspension, saying, “I would also like transparency on the platform end because we are never told what happened when a suspension happened. They say they don’t reveal much in order to prevent scammers, but you don't punish the good people to punish the bad people: we deserve to be told why we are losing our livelihood.”

Another worker described a company practice of withholding money workers had earned, explaining, “It’s frustrating because as workers, suspension is one of the biggest fears because you don’t always get the money in your account; one guy had close to 1k in his account and then it was gone; He got his account reinstated two years later and he should not have had to wait for it; we work through those things and I love that as a community of workers we come together to share information.”

A former Outlier worker described a Kafkaesque scenario in which they were suspended for three months without pay and had no formal pathway to appeal, “In February when I logged in and got a notification of account suspensions for violating community guidelines; I emailed support; from support, I got what sounded like an automated template email that was not case specific, so I thought my time ended there; I sent a message to one of my a favorite managers like ‘it was great working with you, but I don’t expect you to do anything about this,’ but after three months suspended with no work, I got a message from that manager saying ‘I’m gonna get you back’ and he got me unsuspended, so that leads me to believe there was no reason but automated flagging to begin with until someone could dispute it.”

Lack of Control over Work

Workers took pride in their work in shaping AI outputs, but often felt that unclear and arbitrary employer metrics prevented them from doing a good job. One GlobalLogic worker who works on Google projects spoke about how she was able to develop expertise in evaluating an LLM for factual accuracy, tone, grammar, punctuation, and relevance, and enjoyed her work until the tasks given to her were changed without warning. She now works on totally different tasks each day, which have little to do with the skills she has developed over the last year. Workers struggle with confusing evaluation metrics, unrealistic time estimates to finish tasks, and a lack of guidelines and training, even as they remain stuck in insecure jobs with little scope for career progression or advancement.

"We deserve to be told why we are losing our livelihood.” |

|---|

Unclear evaluation metrics

Workers are evaluated on metrics related to the quality and speed of their work, but these metrics are often vague and ill-defined.

When asked if the metrics to remain in good standing at this job were clearly stated by the employer, most survey respondents said no, the metrics are somewhat unclear (50%) or very unclear (36%), while only 14% felt that the metrics are completely clear. |

|---|

Some workers say they do not receive explanations for why a task they complete is rejected. A worker who worked on multiple platforms said, “Typically, there’s no clarity, and that is frustrating because you can do work and not know why it's rejected. How can you improve if you don’t know that?” Similarly, a worker for Digitive said, “I had no idea what the metrics were used for… no one gave me straight answers on what was being collected and for what.”

Speaking about workers having to make up for AI failures and being held responsible for AI mistakes, Tahlia Kirk, an Accenture technical writer who works on Google projects, said: “Since we started using AI tools, it feels like our writers spend a quarter of their day responding to client complaints about quality errors. The client wants us to prove that these errors were introduced by their tool instead of by our writers. This requires lengthy detective work because we have to comb through the content's version history. Ultimately, though, it doesn't matter, because we're supposed to fix all the tool’s errors before the content reaches the client.”

Tahlia Kirk, Technical Writer, Accenture

“The projects we worked on were subjective but they like to say it is objective,” said a former Outlier worker explaining how their expertise is subordinated to getting more work done. “There were also situations where I am a subject matter expert in business and then a non-subject matter expert marked my response down and then I have to go through an appeal process. Often, instead of an accurate appeal process, due to the labor that entails, managers say, ‘it’s a numbers game, so do more good things to pump out good numbers for higher average,’ rather than deal with an appeal.”

Time pressure

Of the 69% of survey respondents whose job requires them to meet “average estimated times” (AETs) for handling tasks, more than half felt AETs are often not long enough to complete the task accurately. |

|---|

More than sixty percent escalate or skip tasks because the AETs are not long enough at least once in a while, with 33% doing so frequently every week.

A Digitive contractor for GlobalLogic said: "[AET is] the almighty driver. Specifically in the context of all the layoffs. You don’t know what you can do other than meet whatever ridiculous AET they are putting forth, and a lot of times they know they are bad AETs but at the same time, you really don’t get any clarification until you are halfway through the task and then you are still stressing out about it because you know that everyone is under the same pressure. So are you in the middle of the pack? Are you leading the pack? It provides a level of uncertainty that makes it stressful. And it’s unfortunate because every person responds differently to that. So you get a lot of people to try to go above and beyond and drive themselves into the ground, and ultimately they burn out.”

Workers may also be impacted by the pressure generated between businesses to win competitive contracts with big tech clients. For example, another Digitive worker said, “We had a meeting with the guy in charge of all rating projects for Google, and he said, ‘You better get your times down or you won’t have a job because we don’t have this project yet.’”

In interviews, some workers also indicated that exceeding AETs on tasks can lead to work being unpaid. “There is a timer with RatersHub to track time on tasks. I think what is going on is that they go by average estimated time, so if you have a task you really can’t go over that time, and if you [do], you do not get compensated. For example, I have to review a YouTube video to make sure it doesn’t break the rules. That video could be three hours long, but they say you only have five minutes to make sure it’s good. Essentially, what happens is, you have to rush through the video because let’s say I take 10 minutes for the video, I’m only going to get compensated for five minutes because that’s the time they put in that I would be paid for it. It leads to issues with actually doing my job and being accurate with it because they’ll say, ‘if you go over, you’re just not getting paid for it.”, explained a Telus worker.

The same frustration was reflected by a former Outlier worker who said, “There were definitely projects that the average turnaround should be five minutes per task, and then they give us a task that’s basically an essay length that we have to read. How can you read this essay, grade it accurately, and then provide feedback in five minutes? The time per task was not adding up, and then the timer put on pressure. Especially because there are occasions on certain projects in which, say, the maximum task time is one hour, and let’s say you exceed that one hour on this task, the task will expire, and you aren’t compensated. You’ve lost an hour of your time, you lost an hour of work, and you aren’t paid, which is quite harsh. And sometimes on certain projects, the amount of time we spend on a task wasn’t reliant on us; it was reliant on something happening with the AI. For example, we were doing adversarial probing work, and they gave us a two-hour time slot on the task, but we had to keep using that specific task until we got the AI to break. If we don’t get the AI to break in two hours, we just lost two hours, and we’re not getting back paid anything. So that’s a lot of pressure because if I don’t get this in before the timer expires, I’m not getting paid for this time that I’ve already invested.”

Workers thus feel they have little control over what they do. With digital monitoring technology, this lack of control also extends to how they do their work. A worker for Digitive who contracts to GlobalLogic for Google projects described her typical day by saying: “I do the same thing all day every day, with 5 mins to complete a task. I feel like a factory worker for knowledge. I do fact-checking all day with a strict handling time, which they closely monitor.”

Most respondents report they are regularly assigned tasks for which they are not adequately trained. |

|---|

Inadequate training

About half of the survey respondents feel their training was “moderately effective” (49%), while 36% found it “not effective” and only 15% thought it was “highly effective.” Further, most respondents report they are regularly assigned tasks for which they are not adequately trained, with 20% reporting this happens very often (multiple times per day), 26% reporting it happens often (multiple times per week), and another 37% say it happens sometimes (at least once per month), while only 13% report this never happens.

“The employers ‘suggest’ training to us rather than require it to get around paying us,” explained a WeLocalize Rater in Ohio. Other workers expressed concern about the low quality of training, with a Telus worker in Oklahoma writing, “I do wish the training was more in-depth and that they hold to their own guidelines.”

Poor instructions were identified as a major inefficiency by an AI fact checker in Florida, “Instructions seem very often thrown together, with 3-4 revisions back to back to back and hundreds of hours in worker time wasted both paid and unpaid. Honestly, it's embarrassing how bad these companies manage the instructions side of these projects. It makes sense, but it’s definitely an inefficiency in the system and one of the LARGER ones for sure. I would guess that 75% of all work that is poor or unusable is due to poor instructions.”

This was confirmed by a GlobalLogic worker in Texas who explained how training was almost non-existent and workers were nevertheless expected to achieve a 97% accuracy rate based on Google Docs that did not cover the wide range of AI responses workers needed to rate daily.

In the same vein, a Telus worker reported that he is assigned tasks multiple times a week that he feels he’s not been trained for, and that training includes only very garden-variety tasks, not addressing anything complicated. The employer rates workers weekly using quality control (QC) tasks, but doesn’t train them for more complicated tasks.

This worker’s experience mirrors a large-scale issue within Google Gemini. For AI-generated content that is more specialized, Google raters were previously encouraged not to approve content if they did not have the “critical expertise” and instead pass it along to someone with more knowledge about the subject. In late 2024, Google changed its rating policy to encourage raters to rate data based on the parts that they do understand, which runs the risk of reducing the accuracy and effectiveness of the platform.26

“We had a meeting with the guy in charge of all rating projects for Google, and he said, ‘You better get your times down or you won’t have a job because we don’t have this project yet.’” |

|---|

“I do the same thing all day every day, with 5 mins to complete a task. I feel like a factory worker for knowledge. I do fact-checking all day with a strict handling time, which they closely monitor.” |

|---|

Dead end jobs

While many workers expressed an interest in advancing within their companies – and some had reported being given promotions over time – most said there was no clarity on how to grow their careers within their companies and that the initial benefits of a promotion may be short-lived. One worker with a PhD said, “No matter what we do, we’re going to get paid the same. I was offered a promotion pretty quickly but with an increase with workload vs amount that you’re actually paid. Some people did get promoted. A lot of people were promised raises, but then those were the first to get laid off, maybe with no real explanation. No matter if you did a good or bad job, people were randomly let go. It became a curse.”

A lack of communication compounds the dissatisfaction workers feel, an Outlier worker explained, “Another problem was no clear communication of how to move up and earn a higher rate and make upward movement in the organization. It felt like a dead end. Also, there’s a huge lack of communication… It’s hard to work in an environment where you are not getting that response - being told you are on a project without work and then they won’t move you out.”

The widespread use of nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) in data work also posed challenges in finding other employment, a worker for Digitive pointed out, “You can't give detail because of NDAs, which hurts resumes.” The worker also noted that professional development benefits diminished over time: “They took away our professional development - everyone had access to learning platforms from LinkedIn for free when we started and then they took it away for contract employees but full time employees had it so leads could use their down time for these projects but we get yelled at when we spend down time on professional development.”

Other workers noted that while they may have been recruited to this work based on their advanced education, their expertise was not utilized in their work. A PhD worker said, “They were looking for specific areas in biology. They wanted experts. There wasn’t any differentiation in the work except for one task. A lot of the PhDs got pulled in then. Now we are doing the same work, not separated in any way. Non-PhDs, non-Masters are working on the same work… It feels like it's predatory in terms of who they are hiring. Even as a scientist, it's hard. Companies take advantage of people with degrees that are not viable in the job market.”

"Another problem was no clear communication of how to move up and earn a higher rate and make upward movement in the organization." |

|---|

Lack of benefits

Absence of mental health protections

Workers frequently deal with a range of violent, offensive, and other sensitive content, and 70% of survey respondents report that their employers asked them to sign a consent form for sensitive content. While a majority of workers said they could opt out of sensitive content or get reassigned to a different project, 11% said they would be fired if they did not sign the consent form. One AI Prompt Writer employed by GlobalLogic reported, “I felt forced to complete the safety content waiver.” Another worker at Telus said, “I think it’s taken a huge toll on my mental health: seeing videos of people dying, cats being tortured nonstop…” and added that if they opt out of sensitive content, “I might not be working at all - then there’s not tasks available.”

Describing their own sense of duty to take on this challenging work, a Digitive worker explained, “I’m one who has always signed up for sensitive tasks since I know how to deal with it as a former victims advocate, but sometimes you dip into subjects where you lose your faith in humanity, but someone has to train the bot.”

Workers also spoke about how opting out of sensitive content can be difficult or even impossible, as a Cynet contractor for GlobalLogic described, "There are some queues that are sensitive and include racism, discrimination, mutilation, suicide, sexual abuse of children: for the longest time, we had no choice to move on that queue and if someone had a problem, they’d be transferred, but it was seen as not a good thing to do; but then they made changes and third parties were required that we sign a form - the form that we sign was saying that we would do sensitive topic areas but we were told it was mandatory to sign... for people doing these tasks, there’s never any debrief and for some people that was really triggering so you couldn’t just exit out - you had to ask a lead if you could exit out of that task and those were such long excruciating days - so it’s mentally taxing."

A Digitive worker from Texas echoed this, “I have complex PTSD, among other things, so it usually causes several problems for my well-being. The worst part, however, is knowing that I have to stay silent and not complain/continue working, because if not, I could be let go at any moment.”

62% of workers say their employer provides no mental health support. |

|---|

Most workers do not receive mental health support services from their employer, with 62% reporting their employer offers no such services, while 22% receive access to teletherapy, 11% have paid “wellness time,” only 1% have a timed cap on sensitive content work, and 9% have access to some other services.27

Workers explained the impacts on mental health from dealing with sensitive content. “They send an email about wellness things, and it’s an animated character. There’s not a real mental health conversation. They pretend they care and send emails with wellness habits, but this isn’t helping me. It’s really affecting me. I’m losing relationships with people I really care about. I already have other issues, and this is on top of it. They pretend and they posture and make gestures of caring, but it feels like babble rather than taking actual action.”

“Mentally, it can be extremely draining, making me become lethargic, sick, or make me have to stop working altogether”, said a Telus worker in Virginia.

Other workers noted that the conditions of precarity inherent to the job itself are what produce negative mental health impacts: Krista Pawloski explained, “The big things are suspensions, and bad requesters and Amazon not giving a sh*t. I touched a little on certain jobs being emotionally taxing, but the whole job can be taxing. There’s a feeling of FOMO, especially with well-paid work. There were times when good jobs pop up in the middle of the night, we would leave our computers on and start work at 3 am; That fear of missing out takes a mental toll too.”

Workers have many ideas about how to improve conditions. When asked what types of benefits they would like to see, a majority of respondents said they would like paid wellness time (63%) and improved health insurance (51%), while 35% said they would want the ability to opt out of sensitive content-related work.28

Tahlia Kirk suggested, “Companies need to set a limited duration for roles working with sensitive content (6 months to a year max). They should transfer these employees to another role with equivalent pay, but working with non-sensitive content. It's simply not healthy for anyone to be exposed to sensitive content for a long time.”

“I have complex PTSD, among other things, so it usually causes several problems for my well-being. The worst part, however, is knowing that I have to stay silent and not complain/continue working, because if not, I could be let go at any moment.” |

|---|

RISKS OF AI SYSTEMS

Workers also indicate concerns about the broader social impacts of the AI technology to which their work contributes.

Training AI to automate jobs

A majority (52%) of surveyed workers believe they are training AI to replace other workers’ jobs, and 36% believe they are training AI to replace their own jobs. |

|---|

Tahlia Kirk explained that workers are being asked to use AI tools and train them to be as good as human workers, with the eventual goal of doing more work with fewer people. She explains why she thinks she might be replaced, even though the AI tools are nowhere near as skilled as she and her teammates. “As writers, we think, ‘This tool isn't checking for all 400 style guidelines, so we're safe from it replacing us.’ But instead, they're reducing the style guidelines to around 200. It's like they consider the tool more important than the content's quality. I can’t help feeling that they'll eventually say they'd rather have crappy quality without having to pay us.”

A Digitive AI Trainer/Tutor working on Google projects, based in Texas, confirmed this view that they may be automating their own jobs: "We've rated AI tasks that were literally about rating AI tasks, among other things. It's very clear that people want AI to be able to do as much as possible, so that they can pay as few people as possible." Workers describe training models to create art and graphics, and do tasks related to editing, software development, customer service, and employee recruitment, among others. A Model Interpretability Analyst employed by Mercor, based in California, said: “[My] current role involves training an AI model to replicate the job of a recruiter in making the best hiring decisions (as recruiters may not exactly have technical knowledge needed to understand the job they are hiring for), so it certainly feels like we are helping to eliminate recruiters.”

Some workers raised specific concerns about the potential harms that could arise from replacing people’s jobs with the tools they are training. An AI Response Evaluator employed by GlobalLogic subcontractor Cynet, based in Arkansas, said, “We train the model to evaluate medical or health conditions and provide what is, in all actuality, a diagnosis and treatment options, many of which the user could opt to try to self-treat. This could lead to a delay in medical care. I recently had a task in which the model suggested a supplement to treat a medical condition, Tardive Dyskinesia. The model said TD could be controlled with Ginkgo, which is completely false.”

While a significant share of respondents believed that employers want to use generative AI to eliminate jobs, other workers did not see their work as helping eliminate jobs. For example, a senior Rater for Bravens working on Google projects pointed to projections suggesting AI will add more jobs than it eliminates and added, “I think AI is great and that it can never truly replace my skills and talents. But the dehumanizing way I am legally allowed to be treated by the USA and Japan (and Europe) makes me sad that AI will perpetuate inequity and dehumanization of life.”

"It's very clear that people want AI to be able to do as much as possible, so that they can pay as few people as possible." |

|---|

Societal risks of AI

Tech giants have adopted ethics and principles related to AI development, but many workers report that they do not see them followed in practice. While companies profess a commitment to safety and accuracy29, multiple workers interviewed for this report express concern that the tech giants do not adhere to their own principles.

Actions by the tech giants have validated workers’ concerns about the inadequacy of voluntary frameworks for AI ethics. For example, just in the past few years, tech companies have fired30 or laid off AI ethics staff31; backed off of pledges against building militarized AI products32; and failed to prevent data breaches of AI systems33. The companies have also reversed course on other commitments – they have retrenched on certain diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives34; allowed discrimination in advertising for housing, employment and credit35 on platforms; and have not fulfilled full commitments to build new housing36. Furthermore, experts are increasingly skeptical37 that big tech companies will meet voluntary commitments they’ve made to hit net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

As workers train AI tools, they see the inside of this technology.

Significant numbers of survey respondents expressed concern about risks to society from AI, with 74% concerned about AI’s contribution to the spread of disinformation, 60% concerned about job displacement, 54% concerned about surveillance, and 47% concerned about the use of AI to suppress free speech, among other issues. |

|---|

A worker who works for MTurk, among other platforms, explained, “I would love to see the end product and know it's not something horrible. For example, I’ve labeled satellite images, and what are those used for?” Similarly, a worker for Outlier expressed regret that “whatever we work on, you know it’s going to apply to warfare, the police state, which I don’t support. I love seeing tech improve, but not for those purposes.”

Working on a Google project, a GlobalLogic worker said, "I wish the public knew how imperfect these models were. I wish they knew how unreliable they were, and I also wish they knew just how much slack we as AI workers are pulling to not embarrass these companies, and they still manage to embarrass themselves… In my opinion, they shouldn't be rolling these things out as things people can use. It's not ready. It's really imperfect… I would tell people, if you're going to use AI, double-check everything they tell you."

Andrew Lauzon, an AWU member and a GlobalLogic super rater, raised another concern about how workplace instructions could end up impacting the quality of AI models. In an interview with More Perfect Union, he described being told to use Google’s AI model, Gemini, as part of his work on the company’s AI models: “[I]f you didn’t know something, instead of taking the time to do your own independent research, they just told us to ask Gemini. Because they wanted to get as many data points in...they didn’t want you spending an hour doing your own independent research to make sure to get it right. They were like, just ask Gemini, be done in five minutes and move on to the next thing”38. Some research indicates that using AI-generated content for training can lead to “model collapse,” negatively impacting the resulting model’s quality and reliability39.

"I wish the public knew how imperfect these models were. I wish they knew how unreliable they were, and I also wish they knew just how much slack we as AI workers are pulling to not embarrass these companies." |

|---|

WHAT MUST BE DONE?

In our worker survey and interviews, data workers explained how their work contributes to the AI industry and how better working conditions could improve the technology itself. As AI is increasingly integrated across a broad range of consequential systems from employment to housing to health care to government services and the justice system, it is critical that we continue to examine the impact of the labor conditions of data workers–the humans behind AI–in shaping this technology. As a Global Logic contractor for Google said: “People think that robots are the ones building the AI, but humans are behind it. All these AI tasks have been taught by actual people. People who have degrees are helping the AI.”

Data workers should be treated as skilled workers with expertise to enhance this industry. However, workers face significant structural barriers to having their voices heard. To achieve better outcomes for workers and the public, AI companies and contractors must respect the rights of workers to take collective action, exercise freedom of association, and bargain to improve their workplaces.

Data workers are already organizing for change in their industry by unionizing with Alphabet Workers Union (AWU)-CWA. Raters at GlobalLogic, a subsidiary of the multinational conglomerate Hitachi, are fighting for40 standardized pay and fair raises, equitable paid time off benefits for all workers, job security, and clear employment pathways – despite alleging retaliation41 for speaking out.

Other data workers employed by contractors for Alphabet have already won42 critical workplace improvements with the support of AWU. For example:

- In 2023, Google Raters, who train the Google Search algorithm by giving essential feedback on what makes better search results, won their first-ever pay raise43. These workers went from making as little as $10/hr to an immediate raise to $14/hr and a promise of $15/hr by the end of the year.

- In 2024, Google Help contractors working for Alphabet vendor Accenture became the first group of AWU-CWA represented workers to bargain a collective contract and only the second group of Google office workers ever to do so. Notable provisions of the contract44 include: guaranteed fully remote work; six weeks of severance in the event of layoffs; 30-day notice of layoffs; and a prohibition on keystroke and mouse monitoring software.

Elsewhere, Turkopticon was established45 with the mission to “organize mutual aid, resources, and advocacy to make Amazon Mechanical Turk work a good job, while also improving conditions for all workers,” and has helped workers on this platform to surface shared concerns46 and successfully advocate for improvements.

Advocacy organizations are also increasingly providing research-backed recommendations about what policies tech companies should implement in order to ensure that data workers are respected throughout their global supply chains. TechEquity developed a Responsible Contracting Standard47 that applies to contracting in the U.S. tech industry broadly. Fairwork developed a set of five principles48 that it uses to score companies that employ workers through online platforms. The Partnership on AI (PAI) published resources specific to data work, including Data Enrichment Sourcing Guidelines49 and a Path for Developing Responsible AI Supply Chains50. Global labor federation UNI Global Union and the Global Trade Union Alliance of Content Moderators51 released a list of eight Protocols for Safe Content Moderation52, reflecting the direct experiences and needs of workers.

These standards and recommendations call for companies that build AI tools to ensure that their own operations as well as their contractors implement policies that support dignified work in this sector including, but not limited to: fair and equal pay and benefits; access to mental health care and counseling; clear and regular communication and training as well as opportunities for full-time work and advancement; realistic productivity expectations and clear evaluation processes; improved transparency and reporting around contractual relationships; and critically, respecting the right to organize and collectively bargain and refraining from retaliation.

However, these critically needed improvements largely exist as recommendations, and no major tech companies have implemented these policies. Policy and enforcement backed by law and by workers collectively building power on a global scale will be necessary to address the working conditions highlighted in this report. Policymakers must step up to advance accountability through legislation and by ensuring that workers are able to organize for fair terms.

The findings in the survey and interviews presented in this report demonstrate that U.S.-based data workers need:

|

Even as AI is incorporated in an increasing number of ways throughout our society, workers who make these systems usable reported in the survey and interviews that their working conditions create pressure and incentives that can result in flaws and errors. It is vital that AI companies, policymakers, and all of us devote more attention to the perspectives of data workers themselves, who are closest to the production of AI, as we continue to debate what guardrails need to be in place to govern emerging technology.

“People think that robots are the ones building the AI, but humans are behind it. All these AI tasks have been taught by actual people. People who have degrees are helping the AI.” |

|---|

CITATIONS

- Bitter, A. (2024). Amazon’s Just Walk Out technology relies on hundreds of workers in India watching you shop. Business Insider.

- Gutelius, B., & Theodore, N. (2025). KENYA’S DIGITAL FIRST RESPONDERS: Center for Urban Economic Development University of Illinois Chicago, USA.

- Anwar, M. A. (2025). Value Chains of AI: Data Training Firms, Platforms, and Workers. In The Future of Labour. Routledge.

- Attard-Frost, B., & Widder, D. G. (2024). The Ethics of AI Value Chains (No. arXiv:2307.16787). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.16787; Bhutani Vij, A. (2023). Women Workers Behind the AI Revolution: The Production and Reproduction of Data Annotation Platforms [University of Toronto]. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/130603; Bird, M., & Schepers, N. (2025, August). The AI Revolution Comes With the Exploitation of Gig Workers. AlgorithmWatch. https://algorithmwatch.org/en/ai-revolution-exploitation-gig-workers/; Cant, C., Muldoon, J., & Graham, M. (2024). Feeding the Machine: The Hidden Human Labor Powering A.I. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/feeding-the-machine-9781639734979/; Casilli, A. A. (2025). Waiting for Robots: The Hired Hands of Automation (S. T. R. T. by S. Brown, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo239039613.html; Chandhiramowuli, S., & Chaudhuri, B. (2023). Match Made by Humans: A Critical Enquiry into Human-Machine Configurations in Data Labelling. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2023.251; Fairwork. (2025). Fairwork Cloudwork Ratings 2025: Advancing Standards in Digital Labour and AI Supply Chain Governance. https://fair.work/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2025/05/Fairwork-Cloudwork-Report-2025-FINAL.pdf; Gray, M. L., & Suri, S. (2019). Ghost Work. https://ghostwork.info/; Gutelius, B., & Theodore, N. (2025). KENYA’S DIGITAL FIRST RESPONDERS: Center for Urban Economic Development University of Illinois Chicago, USA.; Le Ludec, C., Cornet, M., & Casilli, A. A. (2023). The problem with annotation. Human labour and outsourcing between France and Madagascar. Big Data & Society, 10(2), 20539517231188723. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517231188723; Miceli, M., Dinika, A., Kauffman, K., Wagner, C. S., & Sachenbacher, L. (2022). Data Workers’ Inquiry. Data Workers’ Inquiry. https://data-workers.org/; Miceli, M., Tubaro, P., Casilli, A. A., Le Bonniec, T., & Wagner, C. S. (2024). Who Trains the Data for European Artificial Intelligence? (pp. 1–40). The Left, European Parliament.; Morgan, R. A., van Zoonen, W., & ter Hoeven, C. (2023). Lost in the crowd? An investigation into where microwork is conducted and classifying worker types. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 29(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596801231171997; Muldoon, J., Cant, C., Wu, B., & Graham, M. (2024). A typology of artificial intelligence data work. Big Data & Society, 11(1), 20539517241232632. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241232632; Posada, J. (2022). The Coloniality of Data Work: Power and Inequality in Outsourced Data Production for Machine Learning [University of Toronto]. https://utoronto.scholaris.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/41f9a4be-7f13-48f6-9a65-28ee849aa787/content; Roberts, S. T. (2021). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadow of Social Media. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300261479/behind-the-screen/; UNI Global Union. (2025, June). Global content moderators alliance demands Mental Health Protocols in Tech supply chain. UNI Global Union. https://uniglobalunion.org/news/tech-protocols/

- Streitfeld, D. (2025, July 23). Alphabet Reports 14% Increase in Second-Quarter Revenue. The New York Times.https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/23/technology/alphabet-google-earnings-ai.html

- Generated by ChatGPT based on survey results.

- Gutelius, B., & Theodore, N. (2025). KENYA’S DIGITAL FIRST RESPONDERS: Center for Urban Economic Development University of Illinois Chicago, USA.

- IBM Research. (2021, February 9). What is red teaming for generative AI? IBM Research. https://research.ibm.com/blog/what-is-red-teaming-gen-AI

- Taylor, A. (2018, August 1). The Automation Charade. Logic(s) Magazine, 5. https://logicmag.io/failure/the-automation-charade/

- Fox, S. E., Shorey, S., Kang, E. Y., Montiel Valle, D., & Rodriguez, E. (2023). Patchwork: The Hidden, Human Labor of AI Integration within Essential Work. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., 7(CSCW1), 81:1-81:20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3579514

- Huet, E. (2016). The Humans Hiding Behind the Chatbots—Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-18/the-humans-hiding-behind-the-chatbots?leadSource=uverify%20wall

- Olson, P. (2024, April 3). Amazon’s AI Stores Seemed Too Magical. And They Were. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-04-03/the-humans-behind-amazon-s-just-walk-out-technology-are-all-over-ai

- Metz, C., Henry, J., Laffin, B., Lieberman, R., & Lu, Y. (2024, September 4). How Self-Driving Cars Get Help From Humans Hundreds of Miles Away. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/09/03/technology/zoox-self-driving-cars-remote-control.html

- Tubaro, P., Casilli, A. A., & Coville, M. (2020). The trainer, the verifier, the imitator: Three ways in which human platform workers support artificial intelligence. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 2053951720919776. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720919776

- Based on bottom-up estimates of the workforce size for AI labor contractors operating in the United States.

- Wakabayashi, D. (2019, May 28). Google’s Shadow Work Force: Temps Who Outnumber Full-Time Employees. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/28/technology/google-temp-workers.html

- Weil, D. (2014). The Fissured Workplace. Harvard University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wppdw

- Doellgast, V., Appalla, S., Ginzburg, D., Kim, J., Thian, W. L., & International Labour Organization. Research Department,. (2025). Global case studies of social dialogue on AI and algorithmic management. ILO. https://doi.org/10.54394/voqe4924

- Ten percent of survey respondents chose not to disclose their employer.

- Confidential records held by the Communications Workers of America.

- AWU-CWA. (2025). Alphabet Workers Union-CWA. https://www.alphabetworkersunion.org/campaigns/globallogic-pay-parity

- Jobs for the Future. (2025). RITEI Workers Guide Employment Classification and Rights. Jobs for the Future (JFF).

- We exclude 2 outliers that are much higher and have an n of 137 reported hourly wages.

- We exclude 2 outliers that were much higher and one zero entry, and have an n of 156 reported hourly wages.

- We exclude 2 outliers that are much higher and have an n of 21 reported hourly wages.

- Rollet, C. (2024, December 19). Exclusive: Google’s Gemini is forcing contractors to rate AI responses outside their expertise. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2024/12/18/exclusive-googles-gemini-is-forcing-contractors-to-rate-ai-responses-outside-their-expertise/

- Note, percentages sum to more than 100% because respondents were allowed to select all categories applicable.

- Note, percentages sum to more than 100% because respondents were allowed to select all categories applicable.

- Amazon Web Services. (2025). Responsible AI. Amazon Web Services, Inc. https://aws.amazon.com/ai/responsible-ai/; Microsoft. (2025). Responsible AI Principles and Approach | Microsoft AI. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/principles-and-approach; Google. (n.d.). Google AI - AI Principles. Retrieved August 20, 2025, from https://ai.google/principles/

- BBC. (2021, February 20). Margaret Mitchell: Google fires AI ethics founder. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-56135817

- Schiffer, Z., & Newton, C. (2023, March 13). Microsoft lays off AI ethics and society team | The Verge. The Verge.

- Al Jazeera. (2025, February 5). Google drops pledge not to use AI for weapons, surveillance. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/2/5/chk_google-drops-pledge-not-to-use-ai-for-weapons-surveillance

- Public Citizen. (2025, July 24). Amazon AI Breach: A Harsh Wake-Up Call for AI Regulation. Public Citizen.

- Wong, Q., & Lee, W. (2025, February 15). Google and Meta used to champion DEI efforts. Why Big Tech is pulling back. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2025-02-15/google-and-meta-used-to-champion-dei-efforts-now-tech-companies-are-pulling-back

- Angwin, J., Tobin, A., & Varner, M. (2017, November 21). Facebook (Still) Letting Housing Advertisers Exclude Users by Race. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-advertising-discrimination-housing-race-sex-national-origin

- Friedman, N. (2025, August 12). Big Tech Pledged Billions for New Housing. The Results Aren’t Living Up to the Hype. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/real-estate/tech-companies-affordable-housing-pledges-ecd91f4a

- Brown, C. (2025, August 5). Big Tech’s Net-Zero Goals Are Looking Shaky. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/05/climate/tech-companies-climate-goals.html

- More Perfect Union (Director). (2025, August 20). How Google Broke Google [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvaOUFwXjf4

- Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Papernot, N., Anderson, R., & Gal, Y. (2024). AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature, 631(8022), 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

- AWU-CWA. (2025). Alphabet Workers Union-CWA. https://www.alphabetworkersunion.org/campaigns/globallogic-pay-parity

- Fraizer, E. (2025, May 28). The Human Workforce Behind AI Wants a Union. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/google-ai-workers-union/

- AWU-CWA. (2025). Alphabet Workers Union-CWA. https://www.alphabetworkersunion.org/campaigns/globallogic-pay-parity

- Roscoe, J. (2023, February 27). The Invisible Workers Who Train Google’s Algorithm Fought for $15/Hr and Won. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/the-invisible-workers-who-train-googles-algorithm-fought-for-dollar15hr-and-won/

- AWU-CWA. (2024, December 18). Google Help Workers Ratify Collective Contract With Accenture, First In Alphabet Workers Union-CWA History. https://www.alphabetworkersunion.org/press/google-help-workers-ratify-collective-contract-with-accenture-first-in-alphabet-workers-union-cwa-history

- Turkopticon. (2020, July 11). About Us—Turkopticon. https://blog.turkopticon.net

- Turkopticon. (2022, August 18). Turkers demands to Mturk—Turkopticon. https://blog.turkopticon.net/?p=2623

- TechEquity Collaborative. (2022). Shining a Light on Tech’s Shadow Workforce. https://techequity.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Summary-Report-Contract-Worker-Disparity-Project.pdf

- Fairwork. (2024, June). Cloudwork (Online Work) Principles. https://fair.work/en/fw/principles/cloudwork-principles/

- Partnership on AI. (n.d.). Data Enrichment Sourcing Guidelines. Retrieved August 21, 2025, from https://partnershiponai.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/data-enrichment-guidelines.pdf

- Jindal, S. (2024, July 30). Protecting AI’s Essential Workers. Partnership on AI. https://partnershiponai.org/protecting-ais-essential-workers-a-pathway-to-responsible-data-enrichment-practices/ https://www.jff.org/idea/ritei-workers-guide-employment-classification-and-rights/

- UNI Global Union. (2025b, June). Global content moderators alliance demands Mental Health Protocols in Tech supply chain. UNI Global Union. https://uniglobalunion.org/news/tech-protocols/

- UNI Global Union. (2025a). The People Behind the Screens: Why Tech Companies Need New Protocols for Safe Content Moderation. UNI Global Union. https://uniglobalunion.org/wp-content/uploads/The-People-Behind-the-Screens-FINAL.pdf

- Desario, D., Gwin, B., & Padin, L. (2021). Temps in Tech: How Big Tech’s Use of Temp Labor Degrades Job Quality and Locks Workers Out of Permanent, Stable Jobs. National Employment Law Project.https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/temps-in-tech-how-big-techs-use-of-temp-labor-degrades-job-quality-and-locks-workers-out-of-permanent-stable-jobs/

- Desario, D., Gwin, B., & Padin, L. (2021). Temps in Tech: How Big Tech’s Use of Temp Labor Degrades Job Quality and Locks Workers Out of Permanent, Stable Jobs. National Employment Law Project. https://www.nelp.org/insights-research/temps-in-tech-how-big-techs-use-of-temp-labor-degrades-job-quality-and-locks-workers-out-of-permanent-stable-jobs/